(Updated: Feb, 18, 2022)

(Updated for VS 2022: Apr, 20, 2023)

(Updated how to call Win32 API to display a Window Message Box: Sep, 17, 2023)

The Microsoft Visual Studio come with the built-in Macro Assembler and provide many debugging capabilities (Register & Memory View, Breakpoints and Step over). However there is no explicit assembly project template to choose from. In this article, I will describe the steps required to set up an assembly project on the Visual Studio 2019 & 2022.

I had compiled the knowledge from many sources and do many trial and error.

The Sample Projects (for quick reference)

The sample projects of MASM (both 64-bit Assembly and 32-bit Assembly) can be downloaded from the Github links below:

https://github.com/nthana/SampleASM64/

https://github.com/nthana/SampleASM32/

In these samples, I also demonstrate how to call the Win32 “MessageBox” API from the Assembly codes.

1. Installing Visual Studio 2019

Visual Studio 2019 could be downloaded from the site: https://visualstudio.microsoft.com/vs/

The Community 2019 edition is free of charge.

When prompting to select an installed language, I choose C++. I’m not sure whether selecting other languages would work or not for assembly project.

2. Creating a C++ project as a base project

Create a C++ empty project.

Named the project: “MASM”. So that, in the later step, we can save this project as a project template for further use. Set the save location to any preferred folder (I have precreated the folder C:\VSProj). Select “Place solution and project in the same directory” to prevent two nested folders with the same name.

The Visual Studio will create the folder with the same project name automatically.

3. Setup the Build Customization as Assembly Language

Right click at the project name > Build Dependencies > Build Customizations…

Select the “masm”, then OK.

(It should not already been selected. If it is, you should restart Visual Studio and retry again.)

Right click at the project name > properties > Linker > System > SubSystem : Windows

This will prevent the assembly program to show the console window ( the black text-mode window). Or if you want the console window you can leave it at the default: Console mode.

I prefer the Windows mode because it has look-and-feel of native windows app. For debugging, just use breakpoint and watch windows to look at register and memory values at real-time. However, if we want to test the text mode input/output, we should use the console mode.

4. Creating an Assembly Source File

Right click at the project name > Add > New Item…

Name the file: “Main.asm” . The selected item type is not important. Any type can be selected. But it is important to name it with the “.asm” file extension.

Write a test program. You can copy the code from below. I adapted the code from the wonderful book : Assembly Language for x86 Processors by Kip Irvine. I highly recommend this book for anyone start learning the Assembly language.

Firstly, We will create the 32-bit Assembly Code. And then at the appendix B, we will create the 64-bit Assembly Code.

The 32-bit Assembly Code :

.386

.model flat, stdcall

.stack 4096

ExitProcess PROTO, dwExitCode:DWORD

.data

myList DWORD 2, 3, 5, 8

.code

main PROC

mov eax, 7

add eax, 8

INVOKE ExitProcess, eax

main ENDP

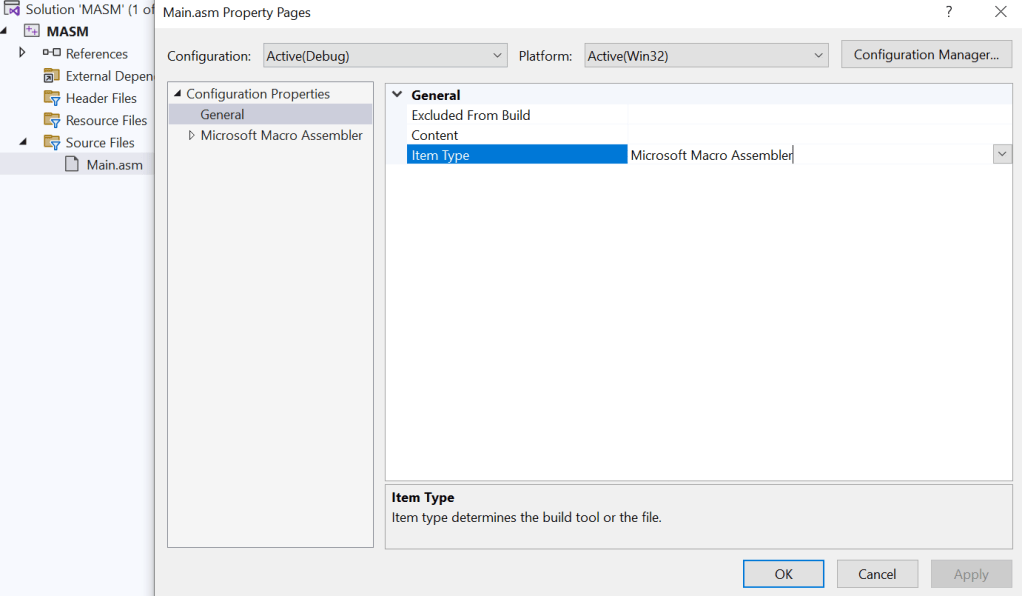

END main ;specify the program's entry pointFor Visual Studio 2022, we need to select our source code item type : Microsoft Macro Assembler.

To build the 32-bit Assembly, make sure that “x86” is selected in the “solution platform” drop down of the toolbar.

Press the green, play button: (run with) Local Windows Debugger.

The program will sum 7 with 8 and return the result 15 as shown in the debug output window.

5. (Optional) Setup Listing File

The listing file is useful for examining what the assembler has generated. To setup the listing file generation, right click the project name > Properties > Microsoft Macro Assembler > Listing File > Assembled Code Listing File : $(IntDir)$(ProjectName).lst

Note: The page “Microsoft Macro Assembler” will appear only when there are some assembly files in the project.

Build (and/or run) the project again. You will see the listing file generated at the project’s debug folder.

Drag the listing file into Visual Studio to view it. The listing file content will be like this:

6. (Optional) Setup for Release Mode Build

This section could be skip because it is quite complex. Do it when you need to use the release mode for release build. Or you could come to this section later when in need.

In Visual Studio, there is a separate release mode build configuration. The release mode configuration could be set differently from the debug mode configuration. For example, the release mode may have more optimizations and less debugging features.

If the release mode is needed, we should do the same as the step 3 and 5. Additionally, we need to customize the safe exception handler configurations.

6.1 Setup Subsystem (Windows or Console) and Listing File Generation

Go to the project properties > change the configuration mode to : Release.

Choosing your prefer subsystem (Windows or Console).

Setting up the listing file generation.

Changing the active configuration to Release.

Try building and running the program using the green play button. You will see the error message: “fatal error: LNK1281: Unable to generate SAFESEH image.”.

The next step 5.2 will solve this error.

6.2 Fully Enable or Disable the Safe Exception Handlers

In the release build mode, the default option of the linker is that every images (object files) should have safe exception handlers. However, the default option of the assembler (compiler) is not to use safe exception handlers. These conflicts cause the above error. Now, we have two choices to fix the error.

Way 1: Enable the safe exception handlers in the assembler (compiler).

Way 2: Or we could entirely disable the use of safe exception handler at the linker.

Linker > Advance > Image has Safe Exception Handlers : No

Choose one way but not both!

I preferred way 1 because it looks safer to have safe exception handlers. But, in fact, I am not 100% sure because I don’t have much knowledge about safe exception handlers.

After that we should be able to build and run the program in the release mode without any error.

Caution on switching between Debug and Release : When changing the active configuration in the toolbar and then open the project property pages, the property pages may not be conformed to the current active configuration. This could cause confusion when changing some project settings appear to not affect the current build. If this occur, please ensure the matching of active configuration and the property pages.

7. Save as a Project Template

After these long steps, we might not want to do them every time to create a new Assembly project. Fortunately, Visual Studio can save the project as a project template.

First, edit the Main.asm to contain only template code:

.386

.model flat, stdcall

.stack 4096

ExitProcess PROTO, dwExitCode:DWORD

.data

.code

main PROC

INVOKE ExitProcess, 0

main ENDP

END main ;specify the program's entry pointTry running it to make sure that the program works correctly.

If you still use release mode (from step 5), switch back to the debug mode.

Click: Project > Export Template …

Choose our “MASM” project from the drop down list.

Describe the template description.

Finished!

After that when you create a new project, you could select MASM as a project template.

Appendix A: Debugging

Debugging is straightforward in Visual Studio. To set a breakpoint, just clicking the grey area in front of the line of the source code. When running, the program will pause before the execution of the breakpoint line.

To look at registers, select Debug > Windows > Registers

To look at variables, select Debug > Windows > Watch. Then type the variable name.

Or select Debug > Windows > Memory > Memory 1. Then type “&varname” at the address box.

Also, we can debug step-by-step using “Step Into” and “Step Over”.

Appendix B: Setup the 64-Bit Assembly Project

This section describes additional steps needed to setup a 64-bit assembly project. You should finish the prior steps before doing these steps.

1. Select the 64-bit platform

At the toolbar, set the Solution Platform to “x64”.

2. Creating the 64-bit Assembly Source Code

Copy the code below to replace the old code in main.asm:

The 64-Bit Assembly Code

ExitProcess PROTO

.data

.code

main PROC

sub rsp, 28h ;reserved the stack area as parameter passing area

mov rcx, 12345678 ; specify Exit Code

call ExitProcess

main ENDP

ENDPlease note that the 32-bit and 64-bit assembly code are different in many ways.

In 64-bit Assembly Code:

- Some directives, such as “.386”, are not used.

- PROTO doesn’t have parameter list specified.

- END doesn’t have “main” start symbol specified.

- When calling Win32 API such as “ExitProcess”, parameters will be passed on registers (rcx, rdx, r8, r9). (see details in Appendix C)

3. Specifying the “main” start symbol (entry point)

When Build, you may get the error: unresolved external symbol mainCRTStartup.

To fix this error:

- Open the project properties page (see image below) by choosing Project > Properties.

- Then make sure that the “Active(Debug)” Configuration and “x64” Platform are selected.

- Set the Linker > Advance > Entry Point to “main“

If you also want to use the release mode build, do the same for the configuration: “Release”, platform: “x64”.

You can also choose the SubSystem: Console or Windows as you preferred.

Run the program. The return code from calling ExitProcess will be displayed on the output windows correctly.

Appendix C: Microsoft x64 calling convention

Microsoft had defined the way that the 64-bit assembly code should call the Win32 API. This specification is called “Microsoft x64 calling convention”. Some essential points are:

- The first four arguments are passed by registers (rcx, rdx, r8, r9).

- Some stack memory, called the shadow area, must be reserved (at least 4*8 bytes)

- 16-byte stack pointer alignment (rsp = stack pointer register) is needed before calling any win32 API.

That are the reasons of this line in the 64-bit assembly code:

sub rsp, 28h ;reserved shadow areaWe need to reserve at least 32 bytes (20h) as the shadow area. And main proc always start at the address ending 8h. So, to do 16-byte alignment, we need to add another (8h) bytes. That’s why we subtract rsp by (28h) bytes. (the stack grows down)

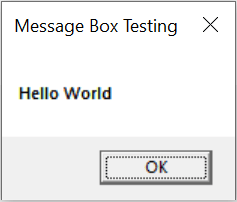

Displaying A Message Box

Consider the following code. This code calls the MessageBox Win32 API.

ExitProcess PROTO

MessageBoxA PROTO

.data

myText db "Hello World", 0

myCaption db "Message Box Testing", 0

.code

main PROC

sub rsp, 28h ; reserved shadow area

mov rcx, 0

lea rdx, myText

lea r8, myCaption

mov r9, 0

call MessageBoxA

mov rcx, 12345678 ; the exit code

call ExitProcess

ENDI have tried to depict the call stack memory layout in the following diagram. Notice that rsp-28h will align the stack pointer into 16-byte alignment beautifully, because the main() procedure is always start with the stack pointer having address ending with 8h. You can see this fact yourself by debugging the above code, running it step by step and observing register values in the register window.

To verify that the alignment requirement is needed, try changing the “sub rsp, 28h” into “sub rsp, 20h“. This will cause the Access Violation run-time error, when calling MessageBox():

Some Win32 APIs are not that strict. For example, the ExitProcess don’t cause the Access Violation Exception. But to respect the x64 calling convention, every 64-bit assembly code that call Win32 API should have some statement like “sub rsp, 28h” to reserve shadow area and adjust stack pointer alignment.

Please note that if use full x64 prolog/epilog code, the “sub rsp, 28h” must be changed to “sub rsp, 20h” because the prior “push” instruction has changed the rsp by 8h bytes. So, need to subtract only 20h.

Normal x64 Prolog/Epilog Code

.code

main PROC

; usual x86-64 Prolog code

push rbp ; save caller's rbp

mov rbp, rsp ; use rbp as a frame pointer

sub rsp, 20h ; reserved as Win32 parameters' shadow area

; Do Something

; usual x86-64 Epilog code

mov rsp, rbp ; restore stack pointer

pop rbp ; restore caller's rbp

ret

main ENDP